Paper Reading: Cost-Effective Hyperparameter Optimization for Large Language Model Generation Inference

Published:

1. Introduction

EcoOptiGen can find higher quality hyperparameter settings than the default settings.

Pruning technique is shown to be effective in increasing the tuning performance significantly.

2. Background

2.1 Text Generation with LLMs

The Input and Output of LLM Text Generation.

Input: inference request. Output: generated responses.

2.2 How Do Hyperparameters Affect Text Generation Performance?

The Impact of Individual Hyperparameters.

(1) model - required input, specifying the model ID to use.

(2) prompt - the input prompt to the model, which provides the context for the text generation task.

(3) max_tokens - the maximum number of tokens (words or word pieces) to generate in the output.

(4) temperature - a value between 0 and 1 that controls the randomness of the generated text. A higher temperature will result in more random and diverse text, while a lower temperature will result in more predictable text.

(5) top_p - a value between 0 and 1 that controls the sampling probability mass for each token generation. A lower top_p value will make it more likely to generate text based on the most likely tokens, while a higher value will allow the model to explore a wider range of possible tokens.

(6) n - the number of responses to generate for a given prompt. Generating multiple responses can provide more diverse and potentially more useful output, but it also increases the cost of the request.

(7) stop - a list of strings that, when encountered in the generated text, will cause the generation to stop. This can be used to control the length or the validity of the output.

(8) presence penalty, frequency penalty - values that control the relative importance of the presence and frequency of certain words or phrases in the generated text. These hyperparameters can be useful for controlling the focus and balance of the generated text.

(9) best of - the number of responses to generate serverside when selecting the ”best” (the one with the highest log probability per token) response for a given prompt.

The Joint Impact of Multiple Hyperparameters.

The interactions and trade-offs make it difficult to manually determine the optimal hyperparameter settings for a given text generation task.

3. EcoOptiGen

- Tuning Data D, a small set of examples which can be used to measure the goodness of each hyperparameter configuration.

- Utility Function U, a function that represents the utility (a real-valued score) of the generated text. For example, for code generation, the utility is the success rate of passing the test.

- Budget Constraints B = (B.i, B.o), a tuple of two values. When B = (1K, 1M), D = 20, if each request consumes exactly 1K tokens, the number of allowed hyperparameter configurations to try during the optimization is equal to 1M/1K/20 = 50.

- Search Space S

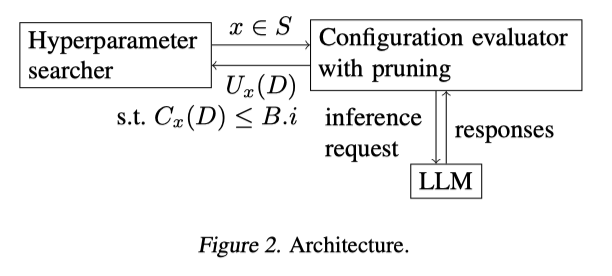

Within the specified optimization budget B.o, the framework iteratively tries different configurations in the given search space S.

Typo: Figure 3 → Figure 2

3.1 Hyperparameter Searcher

Baseline: combines Bayesian optimization and local search, named BlendSearch.

- The local search method in BlendSearch performs randomized direct search with a provable convergence rate and cost bound.

- Bayesian optimization is used to generate starting points for the local search, and different local search threads are prioritized adaptively.

- The original BlendSearch is designed for training hyperparameter optimization and used the training time as the measurement for cost.

Adapt it to optimize the inference hyperparameters, and generalize it to work with any cost metric users desire.

3.2 Configuration Evaluator

3.2.1 PRUNING

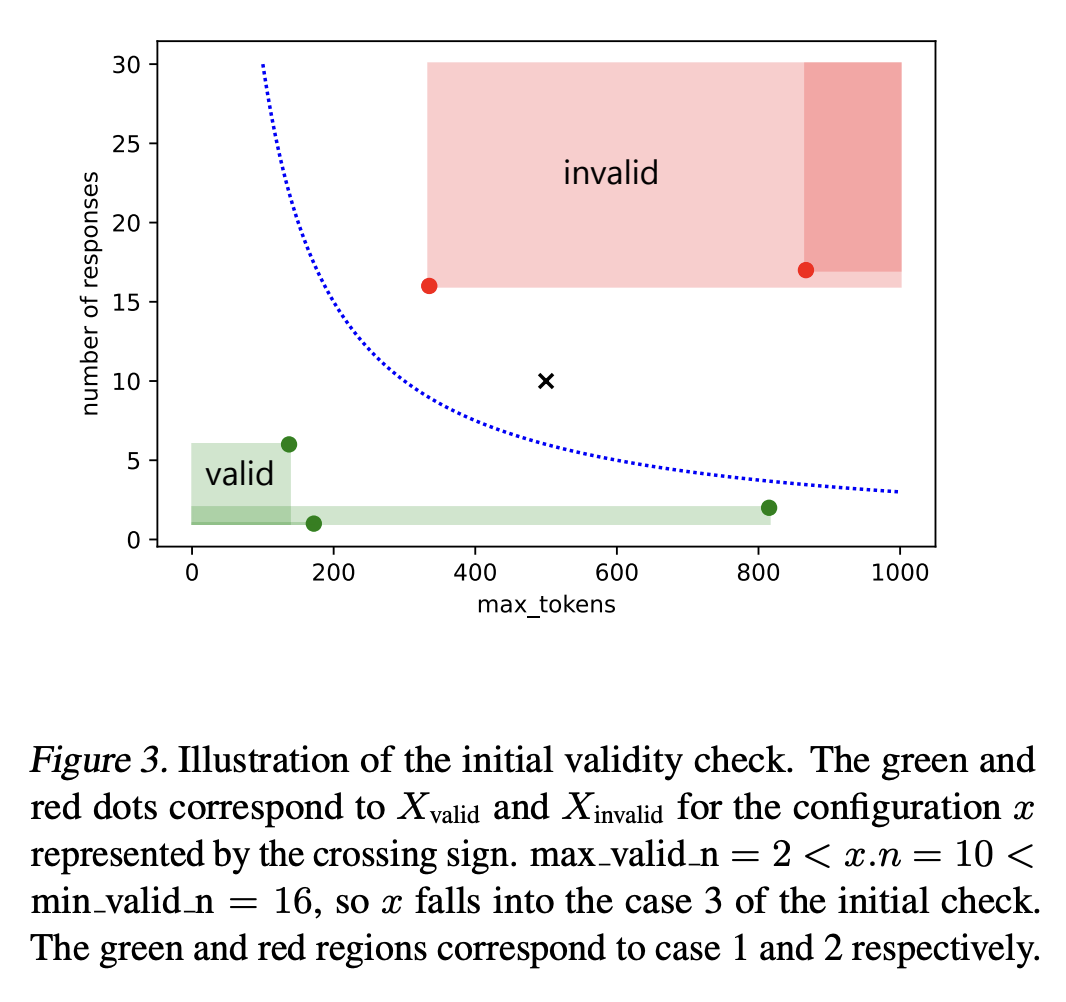

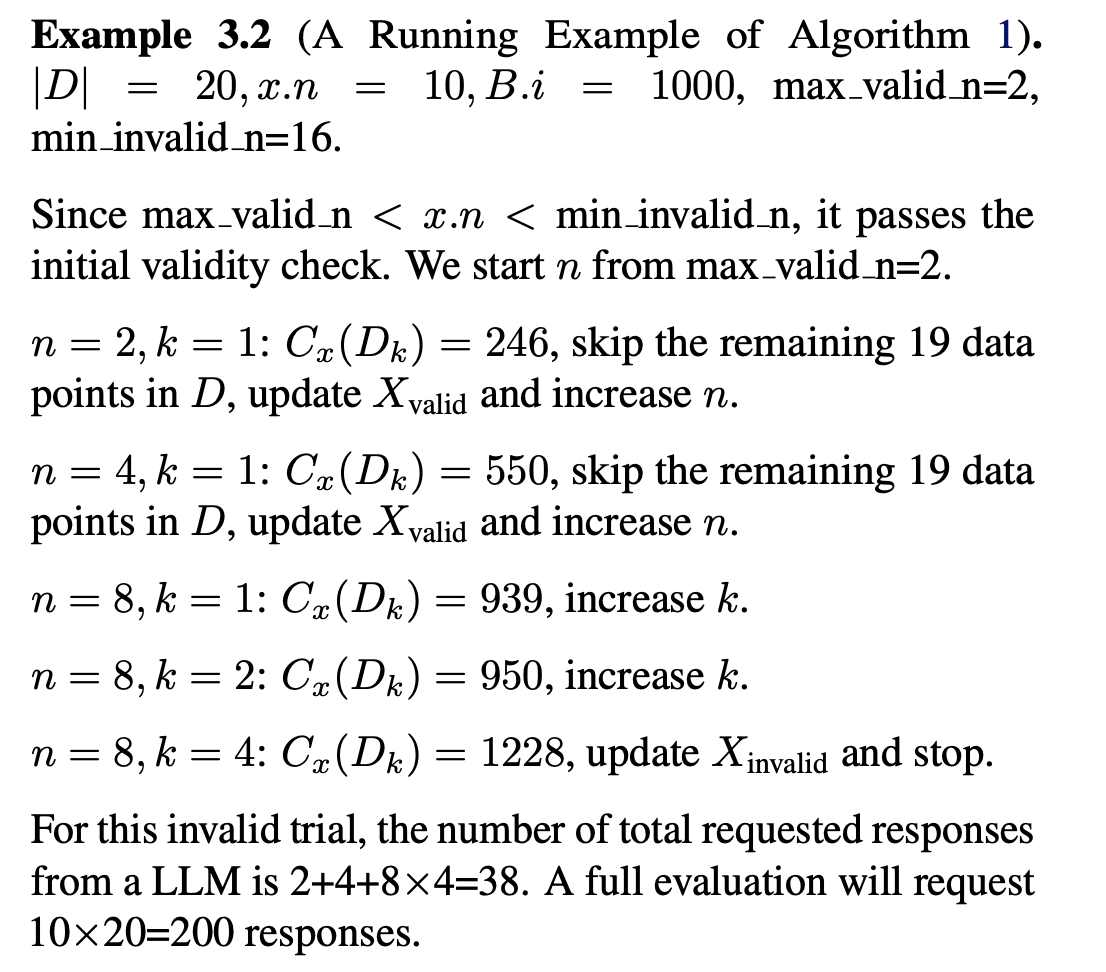

If a configuration x is invalid, it is beneficial to terminate the trial early to save unnecessary cost. We design a pruning strategy by judiciously varying two cost-related factors during a trial: the number of tuning data examples, and the number of responses. A full evaluation of a configuration x needs to send D LLM requests, each asking for x.n responses, where x.n is the setting of the hyperparameter n in configuration x (or the setting of best of if best of is searched instead of n). Our goal is to spend a much smaller cost in invalid trials.

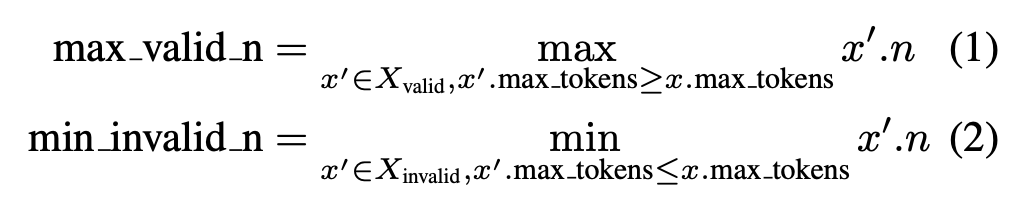

- Initial Validity Check

For a given configuration x, before the expensive evaluation starts, we first check whether we could prune the configuration directly (line 4-10 of Algorithm 1). This check is based on an assumption specific to our optimization problem.

- Assumption 3.1. Given two configurations x1 and x2 with the same setting of model, prompt, and stop, if the number of responses and max tokens in x1 are both equal or larger than those in x2, then we expect x1 has an equal or higher average token consumption than x2.

- A consequence of the assumption is that if x2 is invalid, then x1 is invalid too. If x1 is valid, then x2 is valid too.

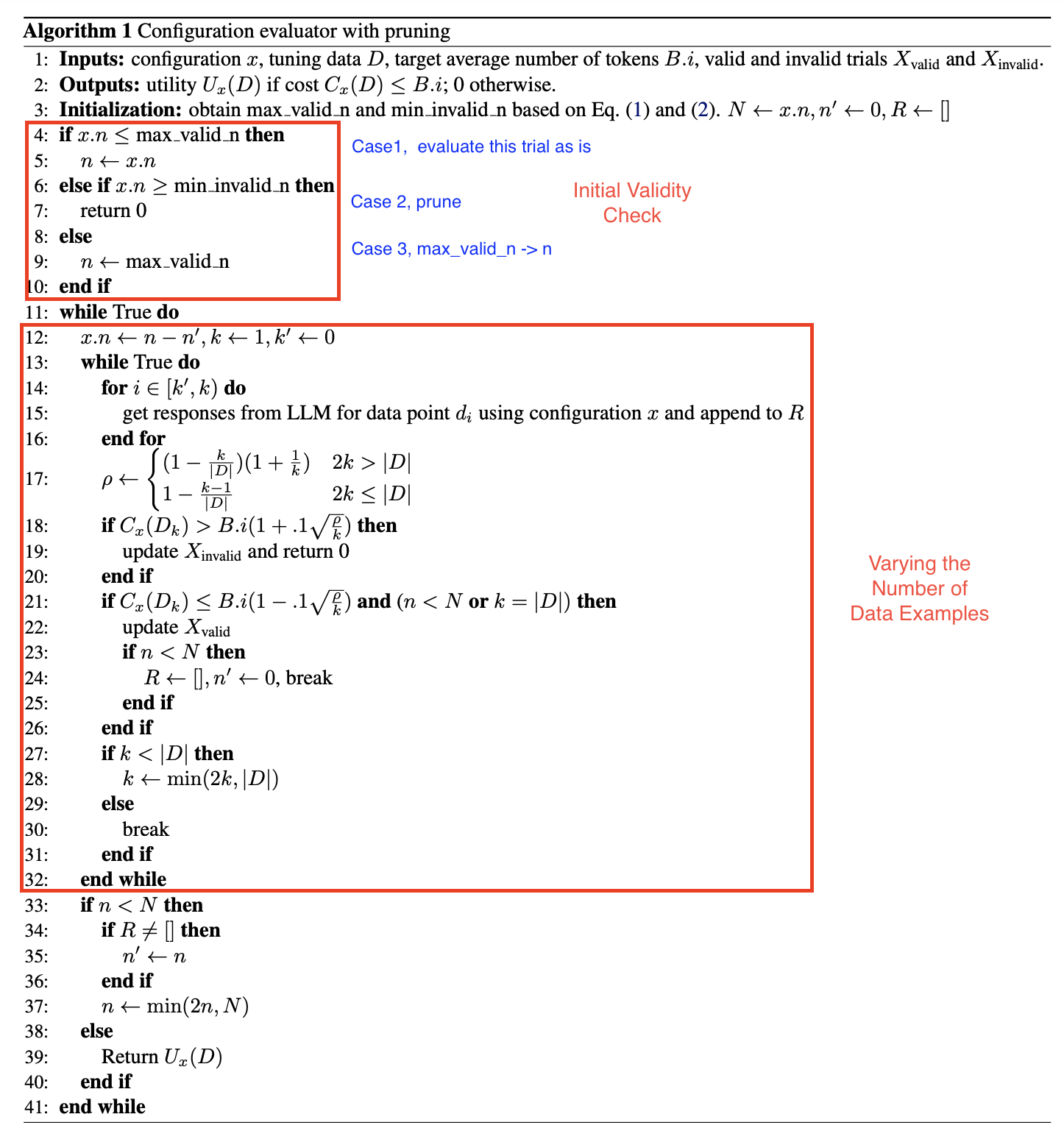

- Our pruning leverages this assumption to find a max known valid_n and a min known invalid_n for a configuration x, using the valid and invalid sets of already tried configurations X_valid and X_invalid which share the same setting of model, prompt and stop with x.

- If x.n ≤ max valid n, we evaluate this trial as is. This corresponds to the case x is expected to be valid based on Assumption 3.1.

- Otherwise (x.n > max valid n), if x.n ≥ min invalid n, we prune this trial without any evaluation. This corresponds to the case where x is expected to be invalid based on Assumption 3.1.

- Otherwise (max valid n < x.n < min invalid n), we start evaluating the trial from number of responses equal to max valid n. This corresponds to the case where x is expected to be either valid or invalid, and max valid n is expected to be a valid number of responses to use for x.

3.2.2 OPTIMIZATION METRIC

For a request with m correct responses out of n total responses, the estimated probability for one response to be correct on this request is m/n. Assuming each response is generated independently, the probability for at least one of the n responses to be correct is then:

1 − (1 − m/n)^n. We take the mean of this number over the tuning data as the probabilistic success rate.

4 Experiments

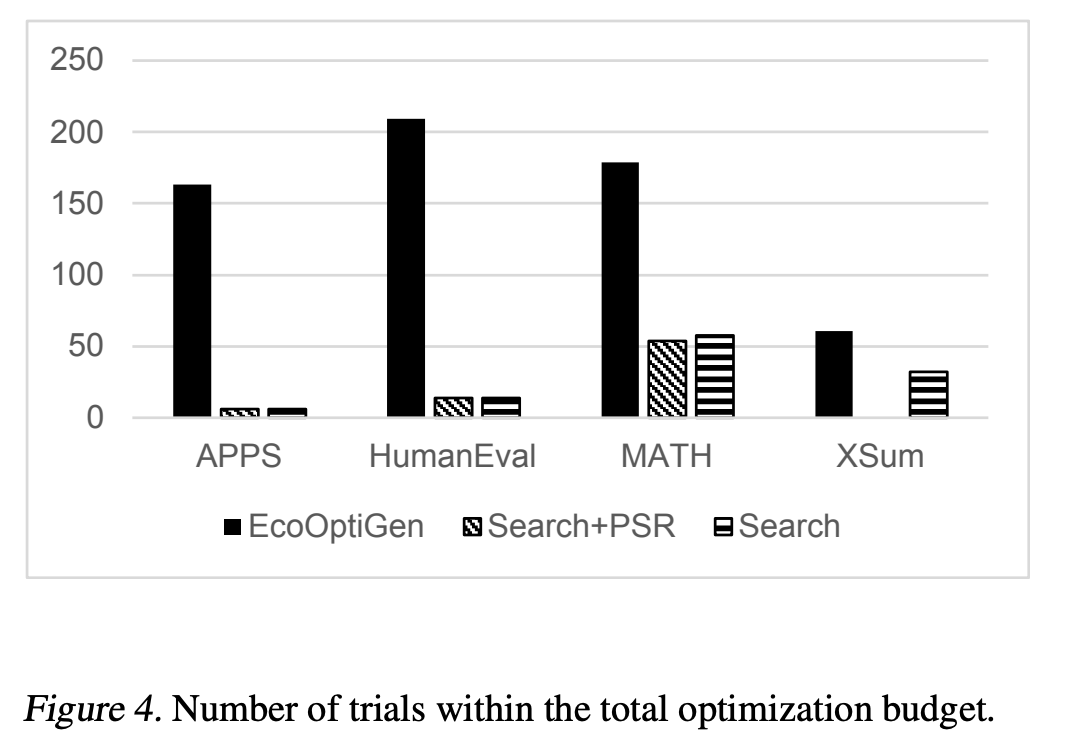

First, for text generation tasks, how much gain can EcoOptiGen achieve by tuning the hyperparameter settings under a budget constraint?

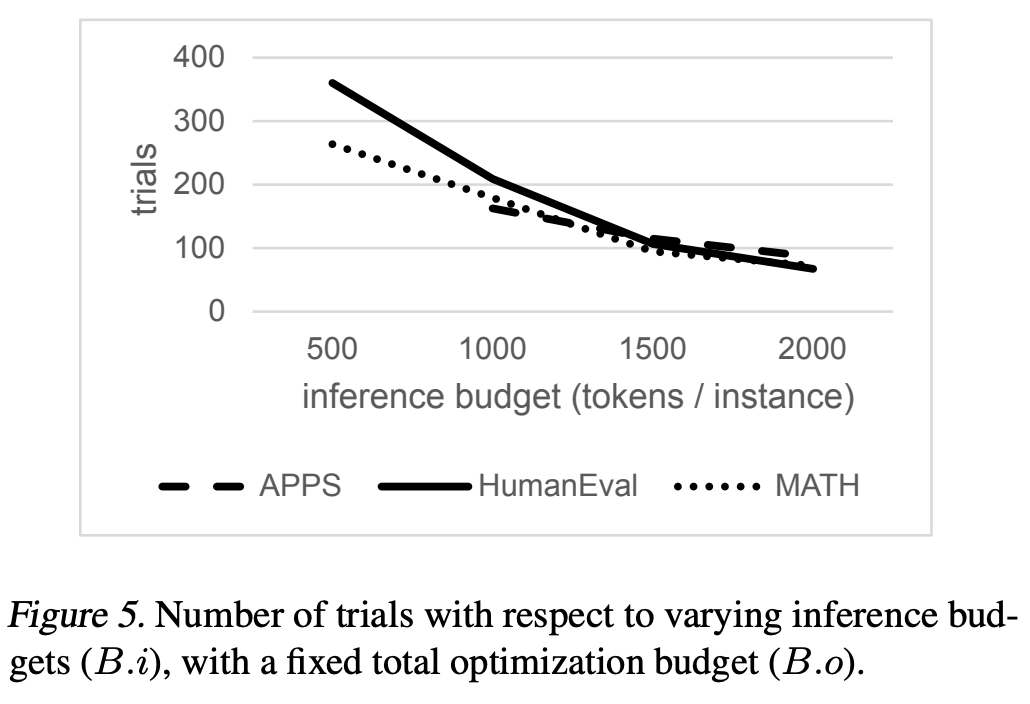

Second, how does varying inference budget affect the optimization result?

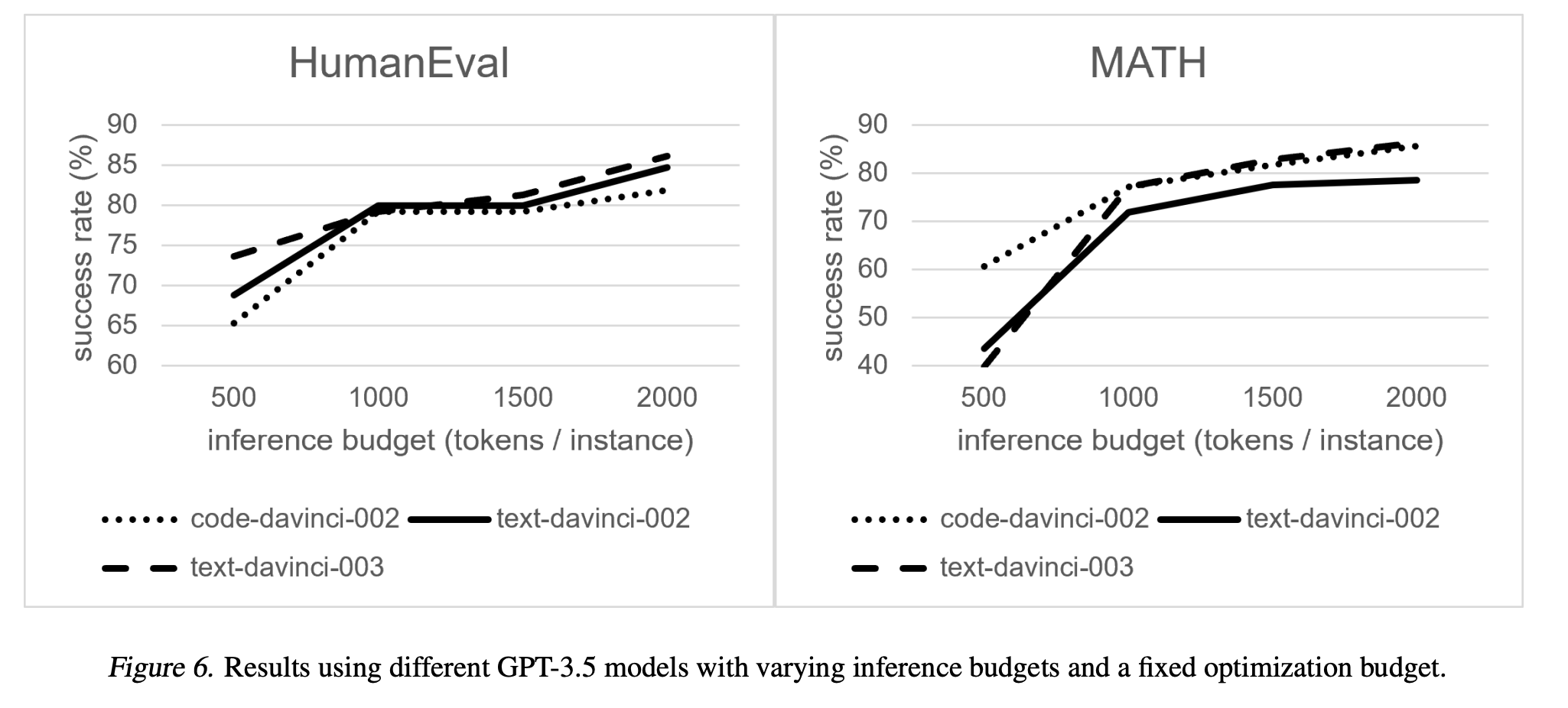

Third, how does varying the model affect the optimization result?

4.1 Setup

4.2 EcoOptiGen’s Performance

4.3 Effect of Inference Budget

The takeaway message in this study is that EcoOptiGen is able to find significantly better configurations with increased inference budget, unless the optimization budget is not enough.

4.4. Effect of Model

The takeaway message of this study is that with EcoOptiGen, the best performing model is not always the commonly recommended model. This reveals one of the benefits of hyperparameter optimization in avoiding suboptimal choices due to idiosyncrasies: Neither a newer model is certain to outperform an older one, nor the optimal choice between code-davinci and text-davinci models can be simply made according to whether the task involves code generation.